1 International Development Institute, Washington, DC, USA

2 Current Affiliation: School of Public Policy, University of Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are central to economic development and employment generation, particularly in emerging economies such as Bangladesh. This study investigates the determinants of small business performance using firm-level data from 1,603 enterprises drawn from the World Bank Enterprise Survey. The analysis examines how firm characteristics, business strategies—specifically business planning, record-keeping and customer orientation—and owner attributes influence performance outcomes. Owner education is introduced as a moderating variable to assess its effect on the relationship between strategic planning and firm performance. Employing a multivariate moderation regression framework, the results reveal that owner education significantly strengthens the positive association between business planning and performance. The findings highlight the importance of owner–manager education in effectively implementing business strategies to enhance the resilience and performance of SME in Bangladesh.

SMEs, business strategy, firm performance, owner education

Introduction

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) form the backbone of most economies, particularly in developing countries. Globally, they account for about 90% of all businesses and employ nearly half of the world’s workforce (World Bank, 2022). When informal enterprises are included, SMEs contribute almost half of the national gross domestic product (GDP) in many economies. In Bangladesh, as in other low and middle income nations, the SME sector plays a pivotal role in driving economic growth and development. SME, together with micro-enterprises, constitute 99% of private sector businesses in Bangladesh (Asian Development Bank, 2015). The sector employs approximately 70%–80% of the non-agricultural labour force and contributes nearly 25% to Bangladesh’s GDP and around 40% to total manufacturing output (Ahmmed, 2018).

Bangladesh recognises micro, SMEs (MSMEs) as key drivers of employment generation, poverty reduction and equitable income distribution, while simultaneously fostering overall economic growth (Dhar et al., 2024). Supported by a vibrant entrepreneurial culture, the country has cultivated a diverse MSME sector encompassing industries such as textiles, agriculture, manufacturing and technology (Alam, 2021). The entrepreneurial ecosystem has evolved through policy initiatives such as the SME Policy 2019 and Industrial Policy 2016, which promote access to finance, training and infrastructure, among others (Dhar et al., 2024; Khondker & Pettinotti, 2024). This ecosystem is shaped by multiple stakeholders, including government agencies, financial institutions, educational organisations, NGOs and private sector actors (Alam, 2021).

Despite their economic significance, MSMEs in Bangladesh face persistent challenges. These include limited access to finance (Dhar et al., 2024), inadequate technology adoption, weak infrastructure, and regulatory and bureaucratic hurdles (Kumar & Suppiah, 2023). Moreover, women entrepreneurs encounter disproportionate barriers compared to their male counterparts, often rooted in cultural norms and unequal access to resources (Sarkar, 2024).

Given the central role of SMEs in economic development, research on their success and failure has expanded considerably in recent years, with growing emphasis on identifying the determinants of firm performance (Keats & Bracker, 1988). Although findings remain mixed, much of this literature highlights firm characteristics as primary predictors of performance (Baker et al., 2021). However, other scholars have underscored the importance of technological capability and understanding consumer behaviour as critical drivers of financial outcomes (Poudel et al., 2019). Additionally, owner demographics—such as age, experience and education—have been shown to significantly influence firm performance (Kalleberg & Leicht, 1991). Overall, the literature broadly agrees that organisational factors and owner attributes jointly shape business outcomes, often exerting greater influence than strategy alone (Blackburn et al., 2013).

In the context of Bangladesh, the research has identified innovation, product quality, cost efficiency, reliability and service excellence as central to SME performance (Islam et al., 2009). Furthermore, entrepreneurial characteristics, rather than firm-level traits, were found to be key drivers of SME success in Bangladesh (Aminul Islam et al., 2011). It has also been observed that strategic execution among Bangladeshi private enterprises remains weak, constrained by limited flexibility and rigid organisational cultures (Dhar et al., 2022). Although managers recognise the importance of coordination and behavioural control, many firms—particularly smaller and younger ones—continue to struggle to align strategic intent with effective implementation.

Building on this context, the present study aims to advance the literature on small firm performance by examining the combined effects of strategic planning and owner characteristics on firm outcomes. Using SMEs in Bangladesh as a case study, it investigates whether strategic planning significantly contributes to firm performance relative to other strategic factors and explores how owner education moderates the relationship between strategic planning and performance outcomes.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. The second section outlines the theoretical framework, reviews relevant literature and develops hypotheses on the factors influencing firm performance. The third section describes the data, methodology and variables used in the analysis. The fourth section presents and interprets the empirical results, followed by a discussion of policy and practical implications in the fifth section. The final section concludes with the study’s limitations and directions for future research.

Theoretical Framework, Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

The definition of small firms differs across countries and sectors, with no universally accepted standard (Storey, 1994). According to Bangladesh’s industrial policy (2010), manufacturing firms with assets up to Tk 300 million (US$3.86 million) and 250 employees, and service or trade firms with assets up to Tk 150 million (US$1.93 million) and 100 employees, are classified as MSMEs (Asian Development Bank, 2015). This study adopts the World Bank’s definition, which classifies small firms as those employing fewer than 100 workers (World Bank, n.d.).

Although definitions of performance vary, financial indicators remain the primary tools for assessing firm performance, complemented by subjective measures such as stakeholder satisfaction (Delen et al., 2013). This study focuses on financial indicators to assess firm performance.

One of the earliest explanations of firm growth dynamics is Gibrat’s law of proportionate growth, which posits that firm growth is random and independent of firm size (Gibrat, 1931; as cited in Fiala & Hedija, 2019). Building on this, Mueller’s (1972) life cycle theory of a firm suggests that firms initially grow through innovation, improved processes, marketing and management, followed by rapid expansion until market saturation slows growth. The resource-based view further explains performance differences by emphasising that firms possess heterogeneous, imperfectly mobile and non-substitutable resources that create sustained competitive advantage (Barney, 2001; Wernerfelt, 1984).

Macroeconomic and sociopolitical factors, such as GDP growth, inflation, road safety and refugee inflows in Bangladesh, also influence sectoral performance. Kuri et al. (2025) studied tourism performance in Bangladesh and revealed that infrastructure improvements enhance long-term tourism demand and the need to align tourism strategies with sustainable development goals by integrating cleaner energy, road safety and social inclusivity initiatives.

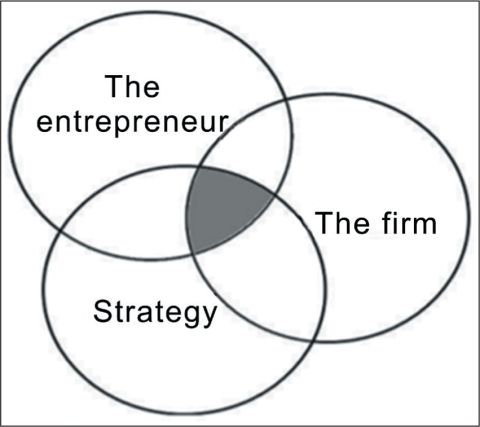

Storey (1994) emphasises the value of examining the growth of small firms through a combination of three interrelated domains: the characteristics of the entrepreneur(s), the firm’s demographics and its business strategy. These three components, each encompassing a set of relevant factors, collectively shape the success trajectory of small businesses. Figure 1 illustrates the interaction among these spheres.

Figure 1. Theoretical Framework.

Source: Storey (1994).

Storey (1994) categorises various determinants within each of the three components. Entrepreneurial characteristics and resources encompass factors such as motivation, educational background, managerial experience, number of founders, prior self-employment, family business history, social marginality, functional skills, training, age, prior business failure, sector-specific experience, previous firm size exposure and gender. Firm-specific characteristics include variables such as age, sector, legal form, location, size and ownership structure. Strategy-related factors capture elements such as workforce and management training, access to external equity, technological sophistication, market positioning and responsiveness, planning, product innovation, managerial recruitment, government support, customer concentration, competitive environment, access to information and advice, and export orientation.

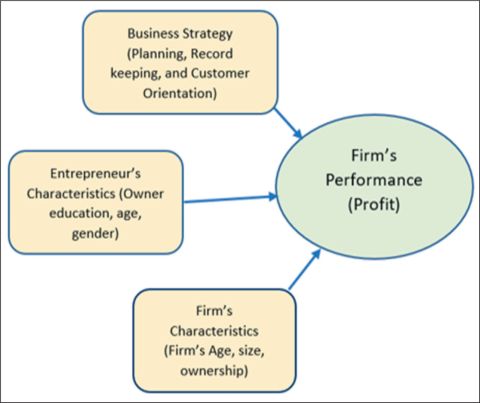

The conceptual framework underpinning this study is grounded in Storey’s (1994) model, which posits that the interaction among three core components determines firm performance. The study investigates the relationship between each of these components and firm performance and further extends the model to examine the moderating role of owner’s education in the relationship between business planning and firm performance. A visual representation of the conceptual model is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Conceptual Model.

Business Strategy and the Firm’s Performance

Recent research has increasingly emphasised the strategic dimensions of small firm growth, and how owner–managers adapt to dynamic business environments (O’Farrell & Hitchens, 1988). This study focuses on three key strategic dimensions: marketing (customer orientation), business planning and financial recording. Among these, financial reporting has received comparatively limited attention, and evidence of its direct link to firm growth remains inconclusive (McMahon, 2001; McMahon & Davies, 1994).

Customer orientation is a key strategic dimension that focuses on understanding and responding to customer needs. It is widely recognised as a driver of customer satisfaction, loyalty and improved firm performance. Empirical studies show that, when supported by strong business and social networks, customer orientation can substantially boost sales and overall firm outcomes (Neneh, 2018).

Strategic planning is a key managerial practice linked to organisational effectiveness, yet evidence on its impact on small firm performance remains inconclusive. While several studies have reported a positive association between formal strategic planning and improved performance (Bracker & Pearson, 1986; Schwenk & Shrader, 1993), others note that many small firms operate successfully without formalised planning systems (Robinson & Pearce, 1984). Furthermore, some scholars contend that informal or unwritten planning approaches can generate performance outcomes comparable to those achieved through formal planning, suggesting that excessive structure may introduce unnecessary rigidity and complexity (Thurston, 1983).

Based on the foregoing discussion, the following hypotheses are proposed to examine the relationship between business strategy and firm performance:

H1: Maintaining systematic record-keeping has a positive effect on SME’s financial performance.

H2: A customer-oriented strategy enhances a small firm’s financial performance.

H3: The implementation of strategic planning positively influences the financial performance of SMEs.

Entrepreneur’s Characteristics and the Firm’s Performance

Scholars have long emphasised owner–manager characteristics—such as age, education, personal objectives, attitudes and values—as key determinants of firm growth (O’Farrell & Hitchens, 1988). Storey’s (1994) framework highlights age, strategic leadership, knowledge and managerial capability as central entrepreneurial attributes influencing firm performance. These traits enable owners to interpret environmental changes, address challenges and adapt strategies effectively (Williams & Ramdani, 2018). Although experience is expected to enhance managerial competence, empirical findings on the relationship between owner age (as a proxy for experience) and firm performance remain mixed (Acar, 1993).

Gender has also been examined as a determinant of firm performance. Some studies suggest that male-owned firms tend to outperform female-owned firms (Khalife & Chalouhi, 2013; Rosa et al., 1996), whereas others highlight women-owned enterprises’ resilience and long-term survival advantage in specific contexts (Kalleberg & Leicht, 1991; Maliranta & Nurmi, 2019).

Based on the above discussion, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4: Owner age contributes positively to SME performance.

H5: Male-owned firms perform better than female-owned firms.

Owner Education and Its Moderating Role

Higher educational attainment strengthens managerial resources, raises income expectations and fosters motivation for superior performance (Kangasharju, 2000). Accordingly, human capital—embodied in education and personal commitment—is viewed as a critical determinant of microenterprise success (Berrone et al., 2014). Empirical evidence supports a positive association between owner education and firm outcomes in both developed and emerging contexts, such as the United States (Fairlie & Robb, 2009) and Turkey (Karadag, 2017), though some studies find no significant link (Barbieri & Mshenga, 2008). Given these discussions, this study predicts the following:

H6: Owner education positively influences SME performance.

H7: Owner education positively moderates the relationship between business planning and SME performance.

Firm Demographics and Performance

As Storey (1994) highlights, firm-specific characteristics—such as age, size and ownership structure—play an important role in shaping small firm performance. The relationship between firm age and performance has been interpreted in diverse ways. Some studies suggest that the likelihood of failure declines as firms mature, implying a negative relationship between age and mortality (Aga & Francis, 2017). Others contend that once firms reach a certain level of maturity, age ceases to be a major determinant of performance (Kalleberg & Leicht, 1991).

Mueller’s (1972) life cycle hypothesis links firm age to performance, proposing that growth rates tend to decline as firms mature. He further contended that firm age was a stronger predictor of growth than size, with younger firms expanding more rapidly than their older counterparts (Mueller, 1972). Subsequent research supports this life cycle pattern, showing that firm performance generally decreases with age (Coad et al., 2018; Yazdanfar & Öhman, 2014). For instance, Cowling et al. (2018) found a negative association between firm age and growth among UK SMEs following the 2008–2009 global financial crisis.

At the same time, older firms often demonstrate greater resilience and accumulated capabilities that enhance their long-term survival prospects, supporting a positive link between age and sustainability (Acar, 1993). Studies also demonstrated that the failure rate decreases as the firm’s size increases, supporting the liability of smallness (Carreira & Teixeira, 2011; Fackler et al., 2013).

Regarding the relationship between firm size and performance, this study considers Kalleberg and Leicht’s (1991) conclusion that size influences growth, contrasting with Dunne and Hughes’s (1994) finding that smaller firms grow faster than larger ones. Regarding ownership structure in shaping firm performance, Storey (1994) noted that firms with shared equity were more likely to grow than those that were unwilling to share ownership. Nonetheless, empirical research on the ownership–performance relationship remains limited.

Based on these insights, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H8: Firm age positively influences firm performance.

H9: Firm size has a significant influence on firm performance.

Data Definition and Methodology

Sample and Data Collection

This study utilises data from the World Bank’s survey of micro and small enterprises conducted in Bangladesh between 2008 and 2014. Given the SME sector’s critical role in employment and income generation, Bangladesh provides a suitable case for analysis. The survey instrument, which was developed jointly by the World Bank and the University of Warwick, assesses business practices in areas such as marketing, inventory management, record-keeping and financial planning, alongside firm and entrepreneur characteristics (McKenzie & Woodruff, 2016).

The survey offers a representative sample of firms defined by specific size thresholds, with the firm (specifically, SMEs) serving as the unit of analysis. Twenty-six questions evaluated core business practices employed in daily operations, including marketing, purchasing and inventory control, costing and record-keeping and financial planning.

The dataset comprises responses from 1,725 small enterprises randomly selected from urban areas across 19 districts in Bangladesh. The sample was stratified by firm size, based on full-time employment, and by industry type, including manufacturing, trade and services. After excluding observations with missing data and those with 100 or more paid employees, the final sample comprises 1,603 firms.

Variables and Measures

Dependent Variable

This study employs firm financial performance, commonly used as a dependent variable in entrepreneurship and small business research, as the primary outcome variable. Despite its prevalence, the conceptualisation and measurement of firm performance remain contested, with scholars debating its definition, dimensionality and appropriate indicators (Santos & Brito, 2012). While performance can be viewed through both financial (e.g., profitability) and non-financial (e.g., stakeholder satisfaction) dimensions (Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1983), financial indicators are favoured for their objectivity, comparability and reliability (Walker & Brown, 2004). Accordingly, consistent with prior studies (Walker & Brown, 2004; Yazdanfar & Öhman, 2014), this article adopts profitability, measured as the natural logarithm of annual profit, as a proxy for firm performance in the regression analysis.

Independent Variables

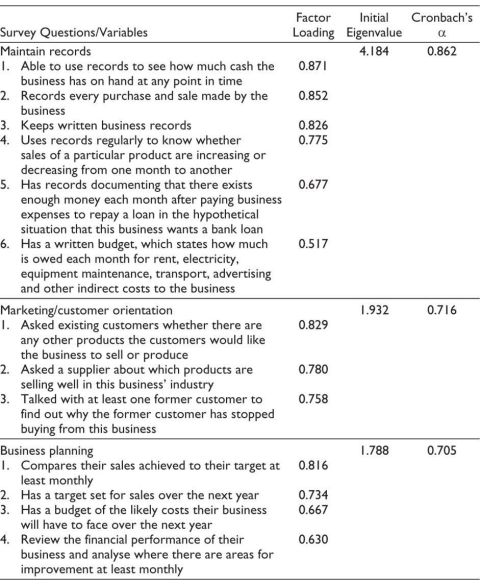

The independent variables used in this study were derived from survey responses, and their construction, along with the related items, is summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Factor Analysis and Reliability Test.

Note: KMO measure of sampling adequacy = 0.82.

Costing and Recording. Financial record-keeping serves as a key explanatory variable, capturing the extent of a firm’s financial documentation practices, as many small enterprises lack complete financial statements. The recording index was developed from six survey questions through factor and reliability analysis, and used to measure the comprehensiveness of their record-keeping, ranging from 0 to 1.

Marketing or Customer Orientation. Customer orientation reflects the firm’s responsiveness to market needs, measured through the owner’s interaction with customers and suppliers. This index, constructed from survey questions on customer feedback, follow-ups with former clients and supplier negotiations, was derived using factor and reliability analysis and ranges from 0 to 1.

Planning. Strategic and financial planning represents an important dimension of entrepreneurial orientation and firm proactiveness. Firms that establish annual sales targets, prepare cost budgets and monitor progress towards these goals are considered to demonstrate higher planning capacity. The index, based on four survey items, ranges from 0 to 1 depending on the comprehensiveness of planning activities.

Control Variable

This study includes control variables that are theoretically and conceptually justified as relevant determinants of firm performance. Firm age, measured by the number of years in operation, is considered a control variable as consistent with prior studies (e.g., Coad et al., 2018). Firm size, proxied by the number of paid employees, is included to account for size-related effects commonly observed in small firm performance studies (e.g., Stam & Elfring, 2008). The owner’s age in years serves as a proxy for managerial experience, which has been shown to positively influence business performance (Gielnik et al., 2017). Owner education, measured as total years of formal schooling (ranging from 0 to 20 years), is included both as an independent variable and as a moderator assessing the impact of business strategy on performance. Next, ownership structure is controlled for given evidence that ownership type may affect firm growth and performance (Davidsson & Henrekson, 2002). Finally, in line with the standard production theory, particularly the Cobb–Douglas production framework, the logarithm of capital stock is included as a control variable to account for variations in firms’ productive capacity and scale, thereby mitigating potential bias arising from differences in capital intensity (Bloom & Van Reenen, 2007).

Reliability and Validity Test

Several tests were conducted to ensure the reliability and validity of the dataset. Factor analysis was first employed for data reduction, based on the premise that multiple observed variables share similar response patterns due to their association with a common latent factor (Hutcheson, 1999). Thirteen observed variables were reduced to three underlying constructs using the eigenvalue-greater-than-one criterion. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.82, which, according to Kaiser (1974), is considered ‘meritorious’. To further confirm the number of extracted factors, a parallel analysis was conducted following the approach recommended by Patil et al. (2008).

A reliability test was conducted using Cronbach’s α to assess internal consistency. Coefficients of 0.70 or higher are generally regarded as acceptable (Cronbach, 1971, as cited in Su et al., 2015). As presented in Table 1, all constructs yielded Cronbach’s α values above 0.705, surpassing the reliability threshold.

Regarding common method bias, the survey design incorporated a combination of dichotomous items and quantitative response questions, reducing the likelihood of bias. As noted by Jordan and Troth (2020), such bias typically occurs when both independent and dependent variables are collected simultaneously using identical response formats (e.g., Likert scales). Given the diverse question structure of the dataset, the risk of common method bias is minimal.

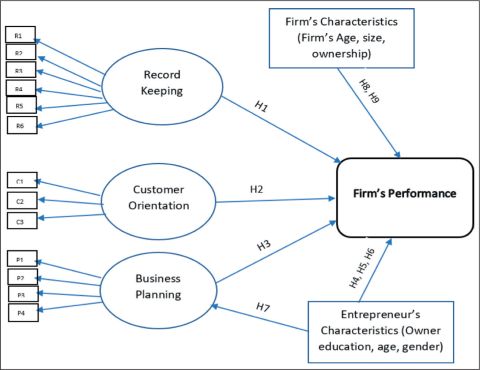

Model Description

The preceding discussion underpins the conceptual framework for this analysis. Based on Storey’s (1994) model of three key determinants of firm success (Figure 3), the framework incorporates owner education as a moderating variable between business strategies and firm performance. Similar frameworks have been applied in prior studies (Khan et al., 2021).

Figure 3. Methodological Framework.

Recent research has further introduced diverse moderating variables, such as strategic flexibility in Bangladeshi SMEs (Dhar et al., 2022), family ownership in Saudi firms (Bazhair & Sulimany, 2023), financial literacy in developing countries (Okello Candiya Bongomin et al., 2017), entrepreneurship education in South Indian SMEs (Selvan et al., 2025) and financial distress in Indian firms (Agarwal et al., 2024). Accordingly, this study estimates two models: a baseline model and an extended model incorporating the moderating effect of owner education.

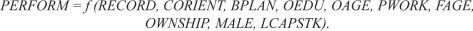

Basic model. The basic model is in the following form:

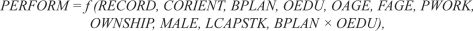

In the moderation model, an interaction term is created by multiplying the business planning variable by the moderating variable, the owner’s education level (OEDU). This constitutes a two-way interaction, as it involves both independent and moderating variables (Dawson, 2014). Both variables are quantitative, and as noted in the literature, there are no restrictions on whether variables in a moderation model must be categorical or continuous (Allen, 2017; Warner, 2020).

A model with an owner’s education as a moderator is as follows:

where PERFORM denotes firm financial performance, serving as the dependent variable. RECORD represents the status of record-keeping, and CORIENT captures the degree of customer orientation. BPLAN indicates whether the firm has a formal business plan, while OEDU refers to the education level of the owner. OAGE and FAGE denote the age of the owner and the firm, respectively. PWORK represents the number of paid workers. OWNSHIP refers to the ownership structure of the firm, and MALE is a binary variable indicating whether the manager is male. LCAPSTK denotes the natural logarithm of the firm’s capital stock. The interaction term (BPLAN × OEDU) captures the moderating effect of owner education on the relationship between business planning and firm performance.

Results

This section presents the descriptive statistics of the variables and the empirical results from multivariate regression analysis.

Correlations and Multicollinearity

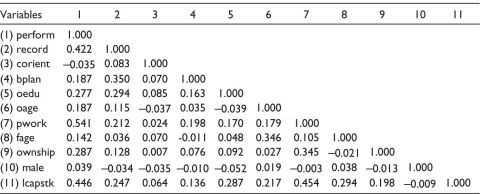

The correlation analysis (Table 2) reveals that firm performance is moderately associated with record-keeping (r = 0.422), number of paid workers (r = 0.541) and capital stock (r = 0.446), indicating that firms with better record-keeping practices, larger workforces and higher capital investment tend to perform better. Owners’ education (r = 0.277) and business planning (r = 0.187) also show a positive relationship with the firm’s performance. Firm and owner age display small positive correlations, suggesting a limited influence of experience and maturity on performance. Customer orientation and gender show negligible correlations with performance, implying minimal direct effects.

Table 2. Pairwise Correlations.

The correlation matrix also helps assess potential multicollinearity among predictors. Prior studies suggest that low to moderate correlations generally do not pose multicollinearity concerns (Cohen et al., 2003; Kim & Miner, 2009). As a rule of thumb, correlations above 0.70 may indicate problematic multicollinearity that could bias regression estimates (Radulovich, 2008). Since the highest correlation in this study is 0.50, multicollinearity is unlikely to affect the reliability or efficiency of parameter estimates.

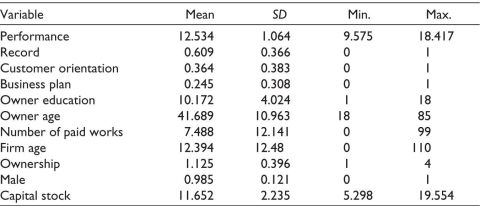

Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics (Table 3) indicate that the average firm performance score is 12.53, suggesting a moderate level of variation across firms. A majority of firms maintain formal record-keeping practices (60.9%) and demonstrate customer-oriented behaviour (36.4%), whereas only 24.5% report having a formal business plan. On average, firm owners are approximately 42 years old and have attained around 10 years of education, while the firms themselves have operated for an average of 12.4 years. Both capital stock and the number of paid workers exhibit some variability, reflecting considerable dispersion in firm size within the sample.

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics.

Regression Results

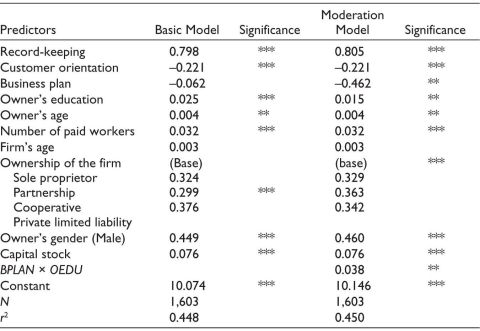

The regression analysis comprises two specifications: the basic model and the moderation model, the latter introducing an interaction term between business planning and owner’s education (BPLAN × OEDU). Table 4 presents the regression results from both models.

Table 4. Regression Results from Both Models.

Note: *** and ** denote 99% and 95% levels, respectively.

Record-keeping shows a consistently strong and significantly positive effect on performance in both models at the 1% level, indicating that a unit increase in record-keeping leads to an increase of 80% in profit. This denotes that maintaining records is a crucial factor in improving firm outcomes. Customer orientation has a significant negative effect on both models at the 1% level, suggesting that customer orientation, perhaps in isolation or without supporting capabilities, may not contribute positively to performance. Business planning is not significant in the basic model, but becomes significant at the 5% level, with a negative coefficient in the moderation model. This implies that business planning does not help enhance performance unless moderated by other factors, such as education.

Owner’s education has a significant positive effect on the basic model at the 1% level, and at the 5% level in the moderation model, indicating its effect is now captured more fully through the interaction with business planning. The interaction term (BPLAN × OEDU) is positive and significant at the 5% level, confirming that education enhances the effectiveness of business planning. Business planning improves performance only when coupled with higher levels of the owner’s education.

Overall, the findings suggest that education amplifies the effectiveness of business planning, while managerial practices such as record-keeping remain fundamental drivers of firm performance. The moderation model offers nuanced insights into how managerial capabilities and human capital jointly enhance the profitability of small firms in Bangladesh. The significant interaction between business planning and the owner’s education indicates that planning alone is insufficient to improve performance unless supported by adequate human capital.

Other control variables, such as the owner’s age, number of paid workers, ownership structure, gender and capital stock, exhibit positive associations with firm performance, with most being statistically significant at the 1% level. However, firm age does not show a statistically significant effect on the performance of SMEs in Bangladesh.

The results also indicate that the three components of business strategy have mixed effects on firm performance. As hypothesised, record-keeping demonstrates a positive and statistically significant impact, thereby supporting H1. In contrast, customer orientation demonstrates a negative and statistically significant relationship with firm performance, while the business plan variable shows a negative but insignificant effect, leading to the rejection of H2 and H3.

Additionally, both the owner’s experience (proxied by age) and education exhibit positive and statistically significant associations with firm performance in the basic model, thereby supporting H4 and H6.

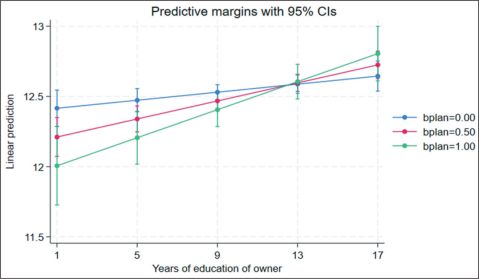

Notably, the moderating effect of the owner’s education on the relationship between business planning and firm performance is both positive and statistically significant. This result supports H7, indicating that education positively moderates the association between business planning and the performance of small firms in Bangladesh. As illustrated in Figure 4, the interaction effect demonstrates that the advantages of having a business plan are contingent upon the owner’s educational level. The firm performance increases substantially when higher education interacts with business planning, indicating that more educated owners are better able to translate business plans into improved SME outcomes.

Figure 4. Graphical Illustration of Interaction Effects.

The positive moderating effect of education on the relationship between business planning and firm performance suggests that education enhances an owner’s capacity to transform plans into effective actions. In the context of small firms in Bangladesh, formal education likely equips owners with better analytical, organisational and strategic management skills, enabling them to utilise business plans more effectively. Conversely, less educated owners may lack the technical and managerial expertise required to translate planning into improved performance outcomes. This finding highlights managerial capability as a mechanism through which education enhances the benefits of business planning. Overall, it demonstrates a classic moderation effect, where education strengthens the impact of business planning on firm performance.

The results also indicate that male-managed firms outperform their female-led counterparts, supporting H5. Since firm age is not statistically significant, the finding does not support the hypothesis regarding the relationship between firm age and performance. However, firm size, measured by the number of paid workers, has a positive and significant effect on firm performance, supporting Hypothesis H9. Compared to sole proprietorships (reference category), partnership firms perform significantly better, likely due to shared resources and decisions. Cooperatives and private limited firms show positive but insignificant effects, indicating no substantial performance difference.

Discussion and Conclusion

Firm performance and its determinants have long been a focus of scholars in small business research. This study specifically examines the moderating role of owner education in the relationship between business planning and firm performance. The observed negative associations between customer orientation and firm performance yield important implications for small business owners and managers.

While customer orientation is important, excessive focus on customer needs can strain limited resources, constrain operational flexibility and reinforce rigid competitor-focused thinking (Brockman et al., 2012; Kadic-Maglajlic et al., 2017). The negative effect observed here aligns with Grewal and Tansuhaj (2001) and contrasts with studies suggesting that customer orientation generally enhances performance (Ziggers & Henseler, 2016). Harris (2001) similarly found no significant relationship between customer orientation and performance. These findings underscore that the effectiveness of customer-focused strategies is highly context-dependent, shaped by the interplay of internal capabilities and external conditions rather than by customer orientation alone.

Similarly, this study suggests that the preparation of a formal business plan does not significantly enhance firm performance in small firms, consistent with prior research questioning the utility of formal planning in small enterprises (Robinson & Pearce, 1984; Thurston, 1983). Excessive focus on planning may shift owner–managers’ attention towards processes rather than outcomes. Incorporating moderating variables, such as owner education, can strengthen the effectiveness of business planning, providing both theoretical and practical insights.

These findings have important implications for national SME development and leadership strategies in Bangladesh. While business planning and customer-oriented practices alone may not guarantee improved performance, enhancing owner–manager capabilities—particularly through education and skill development—can lead to better outcomes. By aligning SME support initiatives with the contextual realities highlighted in this study, policymakers can foster a more resilient SME sector in Bangladesh.

Limitations and Directions of Future Research

This study, by incorporating a broader set of variables beyond those identified in Storey’s framework, provides a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing firm performance. A notable methodological contribution lies in the application of a moderation model, which remains relatively underexplored in this context. Furthermore, the study disaggregates business strategy into three components—planning, customer orientation and record-keeping—and evaluates their distinct effects on firm performance, thereby contributing to addressing important gaps in the small business literature.

Nonetheless, future studies using longitudinal data would allow a more rigorous assessment of the stability and direction of these relationships over time, while tracking firm growth across multiple periods would further deepen understanding of performance dynamics (Vinnell & Hamilton, 1999). Moreover, adopting non-linear regression techniques could yield deeper insights into the potentially complex and non-monotonic relationship between firm age and performance.

Future research could further extend the present study by incorporating emerging variables—such as technological adoption and international market exposure—that increasingly shape small firm outcomes. Additionally, utilising data from other countries with similar economic contexts would allow for cross-country comparisons, thereby enhancing the external validity and generalisability of the findings.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Rajendra Pandit  https://orcid.org/0009-0007-7356-1836

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-7356-1836

Acar, A. C. (1993). The impact of key internal factors on firm performance: An empirical study of small Turkish firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 31(4), 86.

Aga, G., & Francis, D. (2017). As the market churns: Productivity and firm exit in developing countries. Small Business Economics, 49(2), 379–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9817-7

Agarwal, B., Gautam, R. S., & Rastogi, S. (2024). Does financial distress impact the dividend payment of an Indian firm? Future Business Journal, 10(1), 124. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-024-00410-9

Ahmmed, K. F. (2018). Exploring the role of private commercial banks (PCBs) in increasing SMEs’ financial accessibility in developing countries: A study in Bangladesh [ProQuest Dissertations & Theses]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2340238743?pq-origsite= primo

Alam, Q. (2021). Conclusion: The macroeconomic picture of economic growth and relevant initiatives in Bangladesh. In The economic development of Bangladesh in the Asian century (1st ed., pp. 240–249). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003088165-16

Allen, M. (2017). The Sage encyclopedia of communication research methods (1st ed., Vol. 4). Sage Reference. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483381411

Aminul Islam, M., Aktaruzzaman Khan, M., Obaidullah, A. Z. M., & Syed Alam, M. (2011). Effect of entrepreneur and firm characteristics on the business success of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Bangladesh. International Journal of Business and Management, 6(3), 289. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v6n3p289

Asian Development Bank. (2015). Sector assessment (summary): Finance (small and medium-sized enterprise finance and leasing). https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/linked-documents/36200-023-ssa.pdf

Baker, H. K., Kumar, S., & Pandey, N. (2021). Thirty years of small business economics: A bibliometric overview. Small Business Economics, 56(1), 487–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00342-y

Barbieri, C., & Mshenga, P. M. (2008). The role of the firm and owner characteristics on the performance of agritourism farms. Sociologia Ruralis, 48(2), 166–183.

Barney, J. B. (2001). Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: A ten-year retrospective on the resource-based view. Journal of Management, 27, 643–650.

Bazhair, A. H., & Sulimany, H. G. H. (2023). Does family ownership moderate the relationship between board diversity and the financial performance of Saudi-listed firms? International Journal of Financial Studies, 11(4), 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs11040118

Berrone, P., Gertel, H., Giuliodori, R., Bernard, L., & Meiners, E. (2014). Determinants of performance in microenterprises: Preliminary evidence from Argentina. Journal of Small Business Management, 52(3), 477–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12045

Blackburn, R. A., Hart, M., & Wainwright, T. (2013). Small business performance: Business, strategy and owner–manager characteristics. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 20(1), 8–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001311298394

Bloom, N., & Van Reenen, J. (2007). Measuring and explaining management practices across firms and countries. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(4), 1351–1408. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2007.122.4.1351

Bracker, J. S., & Pearson, J. N. (1986). Planning and financial performance of small, mature firms: Summary. Strategic Management Journal, 7(6), 503–522.

Brockman, B. K., Jones, M. A., & Becherer, R. C. (2012). Customer orientation and performance in small firms: Examining the moderating influence of risk-taking, innovativeness, and opportunity focus. Journal of Small Business Management, 50(3), 429–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2012.00361.x

Carreira, C., & Teixeira, P. (2011). The shadow of death: Analysing the pre-exit productivity of Portuguese manufacturing firms. Small Business Economics, 36(3), 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9221-7

Coad, A., Daunfeldt, S.-O., & Halvarsson, D. (2018). Bursting into life: Firm growth and growth persistence by age. Small Business Economics, 50(1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9872-8

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203774441

Cowling, M., Liu, W., & Zhang, N. (2018). Did firm age, experience, and access to finance count? SME performance after the global financial crisis. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 28(1), 77–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-017-0502-z

Davidsson, P., & Henrekson, M. (2002). Determinants of the prevalence of start-ups and high-growth firms. Small Business Economics, 19(2), 81–104. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016264116508

Dawson, J. F. (2014). Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7

Delen, D., Kuzey, C., & Uyar, A. (2013). Measuring firm performance using financial ratios: A decision tree approach. Expert Systems with Applications, 40(10), 3970–3983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2013.01.012

Dhar, B. K., Stasi, A., Döpping, J. O., Gazi, M. A. I., Shaturaev, J., & Sarkar, S. M. (2022). Mediating role of strategic flexibility between leadership styles on strategic execution: A study on Bangladeshi private enterprises. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 23(3), 409–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-022-00310-3

Dhar, S., Zaman, K. A. U., & Dhar, B. K. (2024). MSMEs and economic growth: Fostering an entrepreneurial ecosystem in Bangladesh for sustainable development. Business Strategy & Development, 7(3), e423. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsd2.423

Dunne, P., & Hughes, A. (1994). Age, size, growth and survival: UK companies in the 1980s. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 42(2), 115–140. https://doi.org/10.2307/2950485

Fackler, D., Schnabel, C., & Wagner, J. (2013). Establishment exits in Germany: The role of size and age. Small Business Economics, 41(3), 683–700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9450-z

Fairlie, R. W., & Robb, A. M. (2009). Gender differences in business performance: Evidence from the characteristics of business owners survey. Small Business Economics, 33(4), 375–395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9207-5

Fiala, R., & Hedija, V. (2019). Testing the validity of Gibrat’s law in the context of profitability performance. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 32(1), 2850–2863. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2019.1655656

Gielnik, M. M., Zacher, H., & Schmitt, A. (2017). How small business managers’ age and focus on opportunities affect business growth: A mediated moderation growth model. Journal of Small Business Management, 55(3), 460–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12253

Grewal, R., & Tansuhaj, P. (2001). Building organizational capabilities for managing economic crisis: The role of market orientation and strategic flexibility. Journal of Marketing, 65(2), 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.65.2.67.18259

Harris, L. C. (2001). Market orientation and performance: Objective and subjective empirical evidence from UK companies. Journal of Management Studies, 38(1), 17–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00226

Hutcheson, G. (1999). The multivariate social scientist: Introductory statistics using generalized linear models. Sage Publications.

Islam, M. A., Mian, E. A., & Ali, M. H. (2009). Factors affecting business success of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Bangladesh. Business Review, 4(2), 123–138.

Jordan, P. J., & Troth, A. C. (2020). Common method bias in applied settings: The dilemma of researching in organizations. Australian Journal of Management, 45(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896219871976

Kadic-Maglajlic, S., Micevski, M., Arslanagic-Kalajdzic, M., & Lee, N. (2017). Customer and selling orientations of retail salespeople and the sales manager’s ability to perceive emotions: A multi-level approach. Journal of Business Research, 80, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.06.023

Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39(1), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02291575

Kalleberg, A. L., & Leicht, K. T. (1991). Gender and organizational performance: Determinants of small business survival and Success. The Academy of Management Journal, 34(1), 136–161. https://doi.org/10.2307/256305

Kangasharju, A. (2000). Growth of the smallest: Determinants of small firm growth during strong macroeconomic fluctuations. International Small Business Journal, 19(1), 28–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242600191002

Karadag, H. (2017). The impact of industry, firm age and education level on financial management performance in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): Evidence from Turkey. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 9(3), 300–314. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-09-2016-0037

Keats, B. W., & Bracker, J. S. (1988). Toward a theory of small firm performance: A conceptual model. American Journal of Small Business, 12(4), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225878801200403

Khalife, D., & Chalouhi, A. (2013). Gender and business performance. International Strategic Management Review, 1(1–2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ism.2013.08.001

Khan, R. U., Salamzadeh, Y., Kawamorita, H., & Rethi, G. (2021). Entrepreneurial orientation and small and medium-sized enterprises’ performance: Does ‘access to finance’ moderate the relation in emerging economies? Vision, 25(1), 88–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972262920954604

Khondker, B. H., & Pettinotti, L. (2024). COVID-19, trade and gender in Bangladesh. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 29(4), 1766–1784. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2024.2356336

Kim, J.-Y., & Miner, A. S. (2009). Organizational learning from extreme performance experience: The impact of success and recovery experience. Organization Science, 20(6), 958–978. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0439

Kumar, D., & Suppiah, S. D. K. (2023). MSMEs and SDGs: Evidence from Bangladesh. In H. Dasaraju & T. T. H. Tambunan (Eds.), Role of micro, small and medium enterprises in achieving SDGs (pp. 89–130). Springer Nature Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-4829-1_5

Kuri, B. C., Nahiduzzaman, Md., Dhar, B. K., Shabbir, R., & Karim, R. (2025). Macroeconomic drivers of sustainable tourism development in Bangladesh: An ARDL bounds testing approach. Sustainable Development, 33(3), 3918–3940. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.3328

Maliranta, M., & Nurmi, S. (2019). Business owners, employees, and firm performance. Small Business Economics, 52(1), 111–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0029-1

McKenzie, D., & Woodruff, C. (2016). Business practices in small firms in developing countries (BPSFDC) 2008-2014 [Dataset]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/TER4-1C33

McMahon, R. G. P. (2001). Business growth and performance and the financial reporting practices of Australian manufacturing SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management, 39(2), 152–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-627X.00014

McMahon, R. G. P., & Davies, L. G. (1994). Financial reporting and analysis practices in small enterprises: Their association with growth rate and financial performance. Journal of Small Business Management, 32(1), 9.

Mueller, D. C. (1972). A life cycle theory of the firm. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 20(3), 199–219. https://doi.org/10.2307/2098055

Neneh, B. N. (2018). Customer orientation and SME performance: The role of networking ties. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 9(2), 178–196. https:// doi.org/10.1108/AJEMS-03-2017-0043

O’Farrell, P. N., & Hitchens, D. M. W. N. (1988). Alternative theories of small-firm growth: A critical review. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 20(10), 1365–1383. https://doi.org/10.1068/a201365

Okello Candiya Bongomin, G., Mpeera Ntayi, J., Munene, J. C., & Akol Malinga, C. (2017). The relationship between access to finance and growth of SMEs in developing economies: Financial literacy as a moderator. International Journal of Commerce and Management, 27(4), 520–538. https://doi.org/10.1108/RIBS-04-2017-0037

Patil, V. H., Singh, S. N., Mishra, S., & Todd Donavan, D. (2008). Efficient theory development and factor retention criteria: Abandon the ‘eigenvalue greater than one’ criterion. Journal of Business Research, 61(2), 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.05.008

Poudel, K. P., Carter, R., & Lonial, S. (2019). The impact of entrepreneurial orientation, technological capability, and consumer attitude on firm performance: A multi-theory perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(S2), 268–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12471

Quinn, R. E., & Rohrbaugh, J. (1983). A spatial model of effectiveness criteria: Towards a competing values approach to organizational analysis. Management Science, 29(3), 363–377.

Radulovich, L. P. (2008). An empirical examination of the factors affecting the internationalization of professional service SMEs: The case of India [ProQuest Dissertations & Theses]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/275722252?pq-origsite= primo

Robinson, R. B., & Pearce, J. A. (1984). Research thrusts in small firm strategic planning. The Academy of Management Review, 9(1), 128–137. https://doi.org/10.2307/258239

Rosa, P., Carter, S., & Hamilton, D. (1996). Gender as a determinant of small business performance: Insights from a British study. Small Business Economics, 8(6), 463–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00390031

Santos, J. B., & Brito, L. A. L. (2012). Toward a subjective measurement model for firm performance. BAR, Brazilian Administration Review, 9(spe), 95–117. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1807-76922012000500007

Sarkar, P. R. (2024). From challenges to opportunities: Women entrepreneurs in Bangladesh and their path forward. International Journal of Small and Medium Enterprises, 7(1), 1–11.

Schwenk, C. R., & Shrader, C. B. (1993). Effects of formal strategic planning on financial performance in small firms: A meta-analysis. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 17(3), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879301700304

Selvan, A. M., Susainathan, S., George, H. J., Olson, B. J., Parayitam, S., & Jayaraman, S. (2025). Antecedents of entrepreneurial intention: Entrepreneurship education as a moderator and entrepreneurial self-efficacy as a mediator. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Emerging Economies, 11(2), 252–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/23939575251345228

Stam, W., & Elfring, T. (2008). Entrepreneurial orientation and new venture performance: The moderating role of intra and extra industry social capital. Academy of Management Journal, 51(1), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2008.30744031

Storey, D. J. (1994). Understanding the small business sector (1st ed.). Routledge.

Su, Z., Xie, E., & Wang, D. (2015). Entrepreneurial orientation, managerial networking, and new venture performance in China. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 228–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12069

Thurston, P. H. (1983). Should smaller companies make formal plans? Harvard Business Review 61(5).

Vinnell, R., & Hamilton, R. T. (1999). A historical perspective on small firm development. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(4), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879902300401

Walker, E., & Brown, A. (2004). What success factors are important to small business owners? International Small Business Journal, 22(6), 577–594. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242604047411

Warner, R. M. (2020). Applied statistics II: Multivariable and multivariate techniques. Sage Publications.

Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250050207

Williams, D. A., & Ramdani, B. (2018). Exploring the characteristics of prosperous SMEs in the Caribbean. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 30(9–10), 1012–1026. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2018.1515826

World Bank. (n.d.). [Text/HTML]. Enterprise surveys, methodology: Sampling and weights. Retrieved October 26, 2025, from https://espanol.enterprisesurveys.org/en/methodology

World Bank. (2022). World Bank: SMEs finance. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance

Yazdanfar, D., & Öhman, P. (2014). Life cycle and performance among SMEs: Swedish empirical evidence. The Journal of Risk Finance, 15(5), 555–571. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRF-04-2014-0043

Ziggers, G. W., & Henseler, J. (2016). The reinforcing effect of a firm’s customer orientation and supply-base orientation on performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 52, 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.07.01